As soon as I learned that using trail cameras was an option for my MSc research project on muskrats, I jumped at the opportunity. Of all the fun and exciting ways of tracking and detecting wildlife, I find trail cameras to be some of the most useful and rewarding tools out there. I’ve deployed cameras for various wildlife projects over the years, and tagged thousands of images, but I thought this was my chance to run a whole project, from study design to data analysis.

However, the odds were stacked against me. One single paper titled “Why Camera Traps Fail to Detect a Semi-Aquatic Mammal…” (Lerone et al., 2015) nearly shattered my dreams of a camera trapping project. However, I soon took this as a challenge, and decided that I would make it work. Besides, the study was about otters – muskrats are totally different, right? It did prove challenging finding other studies using cameras to monitor muskrats or even beavers for a point of reference, and for those I could find, most researchers had their cameras set up on solid ground. Since my study site mostly consists of floating cattail mats and open water, this was not an option for me. So, I had to start from scratch.

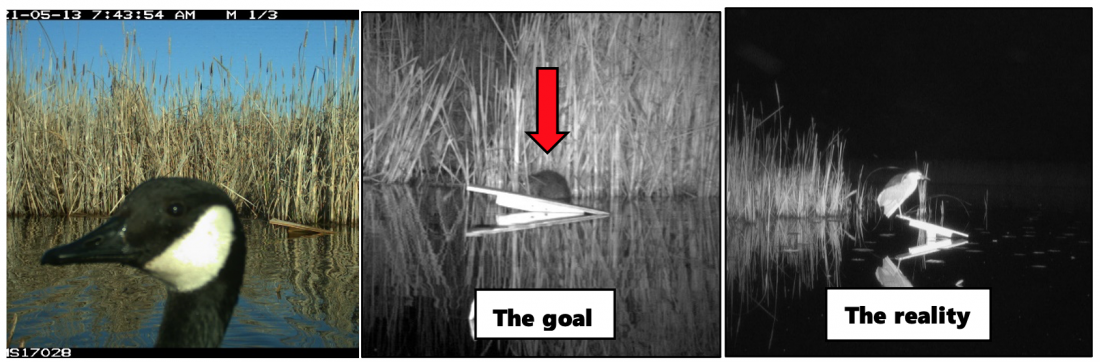

The first step was brainstorming and sketching out all the various prototypes that might be suitable for a camera setup in the water. After much pacing back and forth in my living room and far too many trips to Home Depot, I finally decided on a plan. With my materials list in hand and field truck in tow, I purchased my supplies. Now was the fun part! Being generally handy, I was giddy at the thought of this new construction project. I would build twenty-two camera mounts capable of sliding up and down the length of a 7-foot iron T-post, and locking into place with the help of a few bolts and wing nuts (Reconyx sells T-post mounts for $20 a pop, which I decided was a bit much). Across from each camera, in the marsh, would be a wooden platform sitting at the water’s surface. There are two main reasons for this: 1) The above-mentioned paper by Lerone and colleagues acknowledges the failure of most camera traps when monitoring semi-aquatic mammals – specifically nocturnal ones. This is because at night, most cameras rely on heat sensors rather than motion sensors. When otters, in their case, swim past a camera, only a portion of their body is above water, and this is typically not enough of a change in temperature to trigger the camera. So, in an attempt to be clever, I thought if I could lure muskrats out of the water in sight of the camera, they might give off enough heat to trigger the sensor; 2) In speaking with some researchers and muskrat trappers, it sounded like muskrats are naturally curious and perhaps even attracted to floating platforms (some traps are placed on such platforms, as well as track pads used for detecting muskrats by their prints). In conclusion, my plan was foolproof.

Before deploying all my cameras, I had the foresight of running some tests. I knew from experience that the camera could potentially be triggered by the motion of plants in the wind, and I anticipated this being an issue with all of the cattail in the frame of view. I set up two cameras facing the same platform, setting one to Medium-Low and the other to Medium-High. My first snag came from the realization that my T-posts weren’t long enough! The post shot right down through the muck. Luckily, I had an extra one on board, so I zip-tied both posts together to create a 10-foot mega-post, but I would need to extend all of my other posts as well. Upon looking at the test photos a few weeks later, to my surprise, the cattails did not seem to cause any false triggers, even at the higher setting, so I decided to set all of my cameras to High in the hopes of maximizing my chances of muskrat detections. Now, the real test was determining whether muskrats would climb up on my unbaited platforms, and whether that would cause the camera to trigger. Lo and behold, I was truly ecstatic to find a photo of a muskrat sitting atop the platform! However, this was during daylight, so I still didn’t have evidence of the platforms working at night. Only time would tell. Thankfully, though, I also had the foresight of using the timelapse function – setting the camera to take photos at regular intervals – which I had set to take photos every thirty minutes from dusk to dawn, to mitigate the risk of missed detections at night. Now that my tests were complete and the end of April was approaching (I planned on collecting six months of data before freeze-up) it was time to deploy all twenty-two cameras and hope for the best!

With a map of sampling locations on my phone and 400 pounds of hardware in the canoe, my colleague and I set off to set up the cameras. I had spent a couple days beforehand buying extra lumber and hardware to add wooden extensions to all of my T-posts, ensuring they would be tall enough to keep the cameras above water. When I drove in the first post, however, it didn’t sink far at all, leaving 6 feet of iron above the water. No problem, I thought – this why I have a mallet! I hammered in the post until only a few feet of it were exposed, making sure it was nice and secure and wouldn’t wobble in the wind. I then set up a platform across from the camera, marked down the camera and card ID, and breathed a sigh of relief – the first camera was successfully installed! Just twenty-one more to go! As we moved to the next location and inserted the next post, it stuck way out of the water once again. Ok – another shallow spot. That’s fine. Third location – another shallow spot. I began to fear that perhaps the spot where I had conducted my initial tests was uncharacteristically deep, and my rushing to add post extensions was maybe all for naught.

But I carried on. I had budgeted three days to deploy all of the cameras, and three days is what it took. While day 1 was a lovely, warm, and sunny spring day, a strong and frigid north wind pummeled our canoe the following day. I paddled forward against the wind just to stay in one place while my colleague struggled to drive in the posts and keep the cameras level. Cold and exhausted, but nearly done for the day, I heard a ‘sploosh’ when I momentarily unbuckled my life jacket. I knew that couldn’t be good, but hoped it was just a piece of scrap wood. I soon remembered, however, that I had clipped my brand-new GPS to my life jacket. A wave of panic set in. We slowly passed back and forth over the channel four times with our eyes glued to the water. It was shallow, but full of weeds and detritus and poor lighting, and my GPS was black... Down but not defeated, I convinced myself I would find it on another sunny day. Aside from that unfortunate mishap, all things considered, my first camera deployment was a success!

The whole month of May, I eagerly awaited my return to the marsh to see all the muskrats I had caught on camera (and to find my GPS). I was dying to know whether my platform setup was working as intended. After collecting and replacing the SD cards at the end of May, I raced home to my computer to see the fruits of my labour. Looking through thousands of photos, I played my own version of ‘Duck, duck, goose’. Sadly, while I counted hundreds of waterfowl and other birds (many of whom were quite pleased with the lovely platforms I put out for them), I only managed to count four muskrats in total. I did have a ‘eureka’ moment when I found a muskrat loafing on a platform, but the timestamp was exactly 10:00pm, meaning the camera took this photo automatically and was not triggered by the muskrat’s body heat. Oh well – I still felt a sense of pride for having attracted a muskrat without any apples or carrots, just my wit, my craftsmanship, and, well, probably a lot of luck.

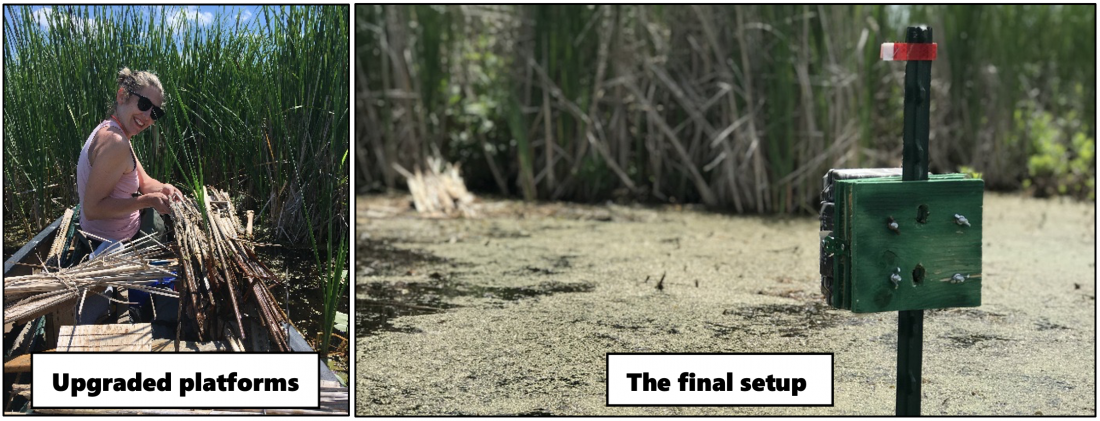

Once I had scanned through a good number of photos, I decided that the small number of muskrat detections could probably be increased by tinkering with my setup and camera settings. For starters, I dismantled nearly all of the posts which I had so painstakingly extended, since the marsh is evidently shallower than I anticipated, and we almost needed a crane to extract the posts we had so deeply anchored in mud (not to mention we nearly got sucked in ourselves). I would now have the platforms set up against the wall of cattail where the muskrats are more likely to pass by, rather than out in the open where wave action is likely to discourage their movement. I made sure to now orient my cameras toward north or south, give or take a few degrees, to avoid the glare of sunrise and sunset – I’ve learned this lesson before, but some lessons need to be relearned, so it were. The glare greatly reduces visibility in front of the camera during those times of direct sunlight, but what’s more, is that on the water, every wave reflecting the sun during those periods trigger the camera, producing thousands of extra, useless photos. Next, realizing that I’m probably still missing muskrats at night, I increased the frequency of regular interval photos from every half hour to every five minutes. This, of course, would produce far more photos, but I deemed it a worthwhile tradeoff to increase muskrat detections. Finally, we covered all of the platforms with dead cattail stalks to give them a more natural appearance, hopefully making them more inviting to passing muskrats.

After a couple rounds of camera deployments and some fine-tuning of my setup, I finally started to see an increase in muskrat detections! My platform idea might have been a bust, but I’m now confident that it is possible to conduct a camera trap study of muskrats. Here are a few nuggets of wisdom I learned along the way:

- Thoroughly investigate your study site before designing or purchasing your equipment and conducting the study (measure water depth at more than one location!).

- Marsh vegetation can grow thick in the summer, particularly wild rice. This can greatly affect camera visibility, but combined with lower summer water levels, it can also make paddling very slow or impossible. Mud motors help!

- Cattail movement doesn’t seem to cause many false camera triggers – but the reflection and movement of waves do.

- Larger, floating platforms may be more inviting for muskrats, and baiting these platforms would certainly help, but certain aspects of study design may need to be considered before using lures.

- Iron T-posts are one of the cheapest and most durable options for mounting cameras in water. Wooden posts (including cedar) are susceptible to chewing by beavers, which I successfully predicted and witnessed with one of my wooden platform posts.

- Make sure your post is deep enough so it is securely anchored in the substrate and won’t sink (or at least, that your camera is water tight – see photo below).

- Triple check your camera settings – and make sure to turn your camera on!

- Tie a floatie to your GPS.

Despite all the times I crashed my computer running ArcGIS, all the sleepless nights wondering whether

I adjusted the camera settings correctly, all the posts I had lengthened (and subsequently shortened), and my GPS now lost in the depths forever (a brief snorkeling venture proved unsuccessful), it was all worth it. Here are some photo highlights to prove it:

Written by Greg Melvin, Trent University

References:

Lerone, L., Carpaneto, G.M., & Loy, A. 2015. Why camera traps fail to detect a semi-aquatic mammal: Activation devices as possible cause. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 39(1):193-196.